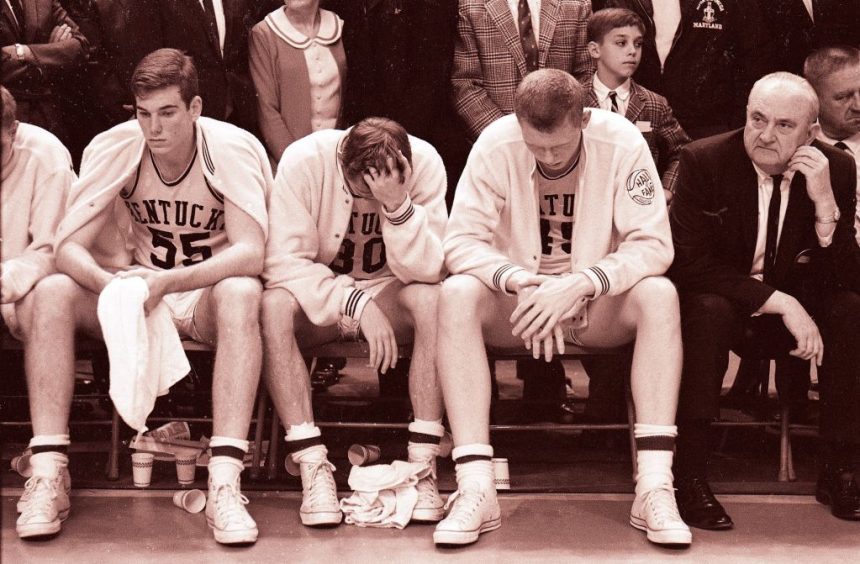

Coach Adolph Rupp, right, watches the awards ceremony after Kentucky lost the NCAA Final Four College Basketball championship to Texas Western at College Park, Md., March 19, 1966. Texas Western, now the University of Texas at El Paso, was the first team of all-Black starters to win the championship. UK players, from left, are Thad Jaracz (55), Tommy Kron (30) and Cliff Berger (45). (Photo by Rich Clarkson/Sports Illustrated via Getty Images)

Recently I’ve had occasion to look into the 1960s world of Lexington and the University of Kentucky, particularly the fraught nexus of the two with race. It’s been an interesting journey through local myth, oral histories and, of course, basketball.

By the time I got to Kentucky in 1992 it had been 20 years since Adolph Rupp had coached the Wildcats and 15 years since his death. But he was still a dominating presence in Wildcat and Lexington lore, his name even enshrined on the basketball arena

As my family could tell you, big time sports, whether so-called amateur or professional, are not my thing. I’ve learned to hate Duke and to avoid driving into town on Tates Creek/High Street on game nights but beyond that I’m a Kentucky men’s basketball agnostic.

Perhaps that’s why it was years before I learned about Rupp’s reputation as a racist. And it was even longer before I came to understand that for decades that reputation was largely responsible for a yawning gap between the university and the Black community in Lexington.

If you type “was Adolph Rupp racist” into a search engine you get a lot of results, most of them pretty sympathetic to the man still known as the Baron of the Bluegrass. Wikipedia for its part walks delicately around the issue. “Rupp’s views on racial issues and interest in signing black players remains a subject of dispute, with Rupp denying accusations of racism during his tenure at Kentucky,” a sentence so nuanced in Wiki world that it requires four citations.

John Oswald was president of Penn State after leaving UK. (University of Kentucky photo)

One person who was much less ambivalent was John Oswald, president of UK from 1963 to 1968. Oswald was no stranger to college sports. As an undergraduate at DePauw University he played varsity football, captaining the team one year, and lettered in basketball and track.

Oswald was eager to see UK’s teams integrated and went himself on recruitment visits to the homes of Nate Northington, one of the two first Black football players at UK, and of Wes Unseld, who wound up playing basketball at Louisville.

Oswald recounts in a 1987 oral history interview that when he got to UK he broached the subject of recruiting Black basketball players with Rupp. “It was clear if he wasn’t a bigot, he sounded like one. He used the word n – – – – – all the time and he used other names to refer to them, a jig and so on.”

Nonetheless, Oswald persisted and suggested Rupp try to recruit Lew Alcindor, who later became one of basketball’s greats as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and at the time was considered the best high school player in the nation. Rupp was willing to consider Alcindor, Oswald said.

“‘If I get a n – – – – -, he’s got to be the best,’” Oswald recalled Rupp saying. The Baron of the Bluegrass fretted about the criticism he might endure if he had a Black player and benched him. “‘They’d all give me hell every day. … I cannot have one unless he is absolutely going to be among the top five but better the top one or two. That’s why I’d take Alcindor if I could get him.’”

Of course, he didn’t get him. Nor did he get any of the outstanding Black players in Lexington, depriving his UK teams of some great local talent.

S.T. Roach (University of Kentucky Special Collections Research Center)

During many of the years he was coaching at UK two Black high schools in Lexington were excelling at basketball in the segregated system. At Douglass, Charles Livisay’s teams finished second in the 1953 National Negro basketball tournament and won the Kentucky High School Athletic League championship in 1954. (The KHSAL was the Black counterpart of the Kentucky High School Athletic Association). His 1957 team competed in the first integrated KHSAA-sanctioned basketball tournament in Lexington, beating Nicholasville 87-45 in the opening round. In 22 years of coaching at Dunbar, S.T. Roach “amassed 512 wins, captured six regional titles, and secured two Kentucky High School Athletic League” championships, the Black Sports Hall of Fame writes. After integration, Roach’s teams competed in two KHSAA Sweet Sixteen tournaments.

The families, friends and fans of those players never had a hope of seeing them play at the University of Kentucky where Rupp fielded all-white teams for 41 of his 42 seasons as coach.

All of this made life even more complex for the few dozen black undergraduates at UK in the ’60s. P.G. Peeples, the longtime head of the Urban League in Lexington, went to UK to finish his degree after attending Southeast Kentucky Community College close to his home in Lynch. While he was proud to be at UK, “I never had any association or identity and pride in that basketball thing,” he explained in a 1993 interview. He soon understood that was also true of the people whose young athletes had been shunned for so many years. “I got here and started to learn … what a gap there was between the Black community and the University of Kentucky, … sometimes I would take that (UK) sweatshirt and put it inside out when I’d come downtown.”

This little history lesson may seem to come out of nowhere. But I thought it was worth recounting in this moment. Another season of UK basketball is upon us in an arena that remembers Rupp while powerful figures in Washington and Frankfort tell us to deny the history of racial prejudice and exclusion that is part of his legacy. Kentucky fans may be willing to forgive the legendary coach but no one should forget this part of his legacy.