This story was jointly reported and published as part of a coordinated investigative and explanatory reporting project of The Maine Monitor and the Bangor Daily News’ Maine Focus team. This project enhances in-depth local journalism and expands public access to the reporting. You can show your support for this effort with a donation to The Monitor. Read more about the partnership.

The Maine State Police reviewed nearly three dozen complaints about troopers who used physical force in the past decade. Not once did the agency determine the force was excessive.

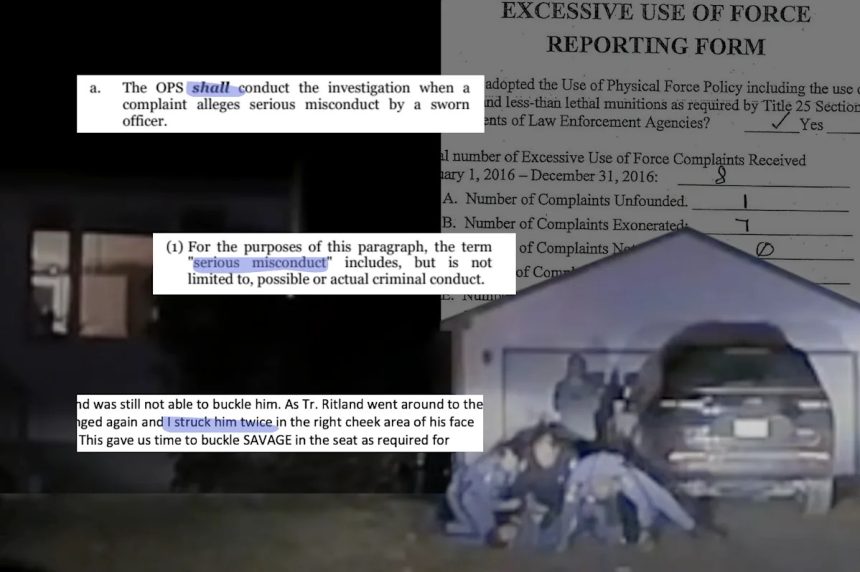

Those cases include the violent March 2024 arrest of Justin Savage, who filed a lawsuit alleging assault, civil rights violations, wrongful arrest, malicious prosecution and defamation against the state police this week.

Dashcam footage published by The Maine Monitor and Bangor Daily News shows a trooper repeatedly punching Savage in the face while he lay pinned to the ground with his hands cuffed behind his back. Savage suffered a broken nose and facial bruising that left him almost unrecognizable, according to jail intake records and photographs taken after his arrest. The state police found the force to be justified.

The pristine record inside Maine’s largest police force struck some experts and legal professionals as implausible in a profession where perfection is hard to achieve. Unlike the state police, other Maine departments have recently sustained allegations of excessive force. Experts said the video of Savage’s arrest casts doubt on the agency’s reviews.

“I would certainly say called into question,” said Dennis Kenney, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and former police officer who reviewed footage of the arrest. “Given this investigation, it would lend credence to suspicion of their internal investigations generally.”

That the state police initially downplayed Savage’s complaint adds to that suspicion, said Emily Gunston, a former lawyer for the U.S. Department of Justice who now consults on police oversight.

The state police’s Office of Professional Standards, the agency’s internal affairs division, is supposed to investigate every complaint of serious misconduct against an officer. But when Savage’s girlfriend, Shawna Morse, submitted a complaint after his arrest, internal affairs delegated the investigation to the officers’ supervisor, a Monitor/BDN investigation found.

Internal affairs only conducted its own review when the state police’s No. 2 official believed the department might be sued. That review also concluded the force was justified.

“This is the type of conduct that in most police departments would be considered either very serious or potentially criminal and should have been investigated at a higher level,” Gunston said. “When there are serious injuries like that, that should be one of the triggers for this getting bumped up to the higher level of investigation.”

The Maine State Police defended its review process. Complaints of excessive force are “investigated with all due diligence,” said Shannon Moss, spokesperson for the Maine Department of Public Safety.

In Savage’s case, the internal affairs division reviewed videos from the arrest and determined that the use of force was “lawful, justified and proper.” Moss did not respond to specific questions about how investigators arrived at that conclusion or the state police’s broader record of clearing officers.

Officers are allowed to use physical force on the job to protect themselves or others or to deal with uncooperative or aggressive suspects. As a policy, the state police reviews every use of force by an officer, regardless of whether there has been a complaint of misconduct.

Between 2015 and 2024, the state police reviewed 776 incidents where a trooper reported the use of force, according to agency statistics obtained by The Monitor/BDN earlier this spring. Only 33 of those resulted in complaints of excessive force.

All of the complaints were either “exonerated,” meaning an investigation found the force was justified, or “unfounded,” meaning the agency determined there was no factual basis for the claims.

Those are two of five outcomes the agency can reach, according to its policy. Investigators can also decide that an allegation is “not sustained,” meaning there was not enough evidence to prove or disprove the complaint; find a complaint to be “sustained,” meaning a preponderance of evidence supports the claim; or decide it is “informational,” meaning the case is sent back to the unit for job performance counseling.

Moss repeatedly declined to provide information on how the agency responded to any excessive force complaints in 2025.

It is implausible that not a single officer crossed the line over the past decade given the size of the department and the kind of work they do, said Matt Morgan, an Augusta-based criminal defense lawyer who said he has reviewed dozens of hours of police footage in his career. Excessive force could apply to a broad range of conduct, from something that causes serious injury to simply holding someone for too long, added David Webbert, a Maine civil rights lawyer.

“They are not trying to learn from these mistakes because they’re not admitting to mistakes at all,” Webbert said.

A different lawyer said the state police’s clean record did not surprise him. Michael Cunniff, a Portland lawyer and former federal law enforcement officer who has worked extensively with Maine police departments, including by conducting internal affairs investigations and defending officers under investigation, described a healthy police culture here.

Officers generally demonstrate restraint in using force, receive frequent training and know they are subject to oversight by their supervisors and by a public that increasingly records police actions on their phones, he said.

“I just know how carefully scrutinized officers are,” he said. “You can’t take a paintbrush and rely on the false premise that there must have been some bad cases.”

Cases should be judged individually, Cunniff said. But that is difficult to do. Complaints about police officers and the resulting investigation records are confidential under Maine law. Only discipline records are considered public.

The state police ruled the Savage complaint “exonerated” and did not discipline any of the officers involved, a finding that multiple policing experts questioned because there are few situations where an officer is justified in striking a restrained person in the head. (Savage agreed to a deal with prosecutors this spring that would dismiss all the criminal charges that stemmed from his arrest, including felony assault on an officer.)

An internal state police panel charged with examining every trooper use of force also failed to look at Savage’s case because it has been inactive for more than a year and a half, in violation of the agency’s policy.

The Committee to Review Use of Force Incidents is supposed to meet quarterly to review the previous quarter’s use of force incidents, recommend any necessary changes to training or practices, and notify internal affairs if it uncovers possible misconduct, the department’s policy states.

The group has not met since January 2024 due to vacancies and other demands on the agency’s staff, said Rebecca Graham, the agency’s director of policy, public records requests and legislative affairs.

Other large police departments in Maine have sustained complaints. The Maine Criminal Justice Academy, which trains and oversees the certification of all Maine law enforcement officers, requires agencies to report annual excessive force complaint statistics. The Bangor, Lewiston, and Portland police departments have all sustained complaints in recent years.

Between 2016 and 2024, Lewiston reported two sustained complaints, while Portland and Bangor each reported one. Lewiston and Bangor also reported three and two complaints, respectively, that were “not sustained.”

In the sustained Bangor case, from 2022, an investigation conducted by the deputy chief in Brewer found that a former patrol officer, Allen-Michael Jones, acted improperly when he tried to escort an uncooperative person out of a First Street apartment, according to a discipline record obtained in a public records request. The person said they were having a seizure, could not walk, and asked for an ambulance, but Jones thought they were faking it and arrested them.

During the arrest, the officer pinned the person against a cruiser, and “forcibly struck” them in the back of the head with his forearm while using inappropriate language, according to the record, which also faulted Jones for failing to properly document the incident. He got a weeklong unpaid suspension and was required to get additional training.

“Your conduct is of concern. Your tone, language and amount of force applied in this instance is without justification,” Bangor police Chief Mark Hathaway wrote in a discipline record. “The passive resistance presented by the individual you were placing in custody did not warrant the level of force utilized to maintain control.”

Comparisons to other similarly sized state police forces in New England are complicated by the level of public access to relevant data.

The New Hampshire State Police doesn’t track complaints against officers, said Allison Greenstein, a staff attorney. She said that state law prevented her from saying whether the New Hampshire State Police had sustained an excessive force complaint in the past decade.

The Vermont State Police provided data that showed the agency recorded 42 excessive force complaints between 2015 and 2024. Of the 36 complaints that have been fully adjudicated, seven — roughly 20 percent — resulted in discipline.

A spotless record is not by itself evidence of lenient oversight, but the handling of Savage’s case casts doubt on the department’s credibility, said Gunston, the former DOJ lawyer.

“When you are able to see one of those, and you can see that there should have been discipline, it is absolutely appropriate to start thinking about whether or not it’s indicative that the complaint system and the administrative investigations may be insufficient,” she said.