With a citizen-led independent redistricting commission, California has long championed taking politicians out of the political map-drawing process. But a Nov. 4 ballot measure is testing the Golden State’s legacy as a model for fair maps.

Gov. Gavin Newsom is pitching his Proposition 50 as a referendum on President Donald Trump’s grip on the legislative branch controlled by Republicans in Congress – calling it the “most transparent” redistricting process nationwide, since California voters will directly weigh in on the proposed new maps next Tuesday.

MAP: Vote-by-mail ballots returned for 2025 California special election to decide Prop 50

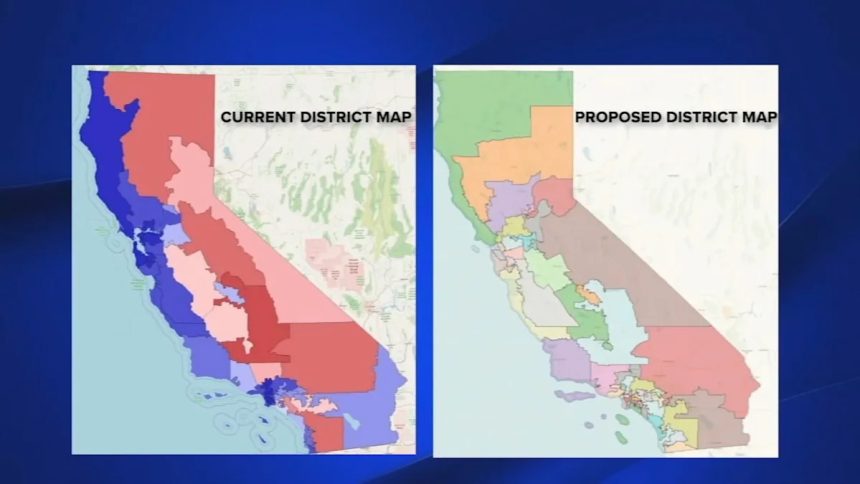

The new district lines were controversially drawn in a flurry and passed by state lawmakers in August, and are designed to help Democrats pick up at least five more congressional seats in the 2026 midterms. The measure aims to counter to Texas, which recently approved gerrymandered maps to shore up Republicans’ slim majority at the behest of President Donald Trump.

California Republicans have largely condemned gerrymandering efforts in both the Lone Star and Golden State, decrying the effort as a power-grab to ultimately give the reapportionment authority back to the state’s Democratic supermajority Legislature.

A citizen commission meant to take politics out of maps

In 26 states, lawmakers control where congressional boundaries are drawn. But California ceded that influence to ordinary residents after voters approved Propositions 11 and 20 more than a decade ago.

Back in 2008, when Californians approved the Voters First Act, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, at the time a political newcomer, spearheaded the charge – citing his frustrations with how gerrymandering distorted not just voter representation but the entire political process.

RELATED: Arnold Schwarzenegger urges voters to reject Prop 50

“We have a broken system. Politicians draw their own districts to protect themselves, not the people,” Schwarzenegger said in 2008 when advocating for Prop 11, which he said was designed to “take that power away and give it back to the voters.”

Cynthia Dai, who served California’s inaugural independent redistricting commission in 2010, recalls the voter-driven effort as a corrective. Motivated by her passion for democracy, Dai applied to join the commission in a process she said was more rigorous than applying to an Ivy League school.

How does California’s independent redistricting commission work?

Not only do applicants have to be vetted by the California State Auditor, but there are strict rules that disqualify anyone deemed to have a conflict of interest in choosing how the state’s nearly 23 million voters are represented.

Elected officials, candidates, lobbyists, major political donors, or anyone who close ties or relations to those individuals are not eligible to join the California Citizens Redistricting Commission. It is made up of 14 members from different political parties: five registered Democrats, five registered Republicans and four otherwise independent voters with “no party preferences.”

That lengthy qualifications and diverse background are what Dai said led to a “principled” commission – and one that was eager to draw the most equitable lines as possible. Most importantly she says, every part of the process had to happen publicly.

RELATED: Obama appears in ad urging CA voters to approve Prop. 50, joining fight for US House control

“Everyone could see exactly what was happening. They could see how the lines were drawn. It was not done in a smoke-filled back room by political consultants who were paid to draw these designer districts. It was drawn in public,” Dai said. “Every difficult decision we made, every trade-off we had to consider, they could see what we went through.”

What is gerrymandering and its impact?

For most voters, gerrymandering is an abstract term invoking not-so-nostalgic flashbacks from high school history class. But in practice, gerrymandering is the invisible hand influencing who represents them and often, which party can win the district before a single ballot is cast.

Eric Schickler – co-director of UC Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies – says to understand why California’s redistricting fight matters, you have to revisit early American history.

The ninth governor of Massachusetts was a founding father named Elbridge Gerry, who drew the state’s senate districts so misshapen that critics likened it to the shape of a salamander. The first recorded appearance of the phrase “Gerry-mander” was in an 1812 political cartoon in the Boston Gazette. Both the name and the tactic stuck around.

“The Constitution left it up to state legislatures to draw congressional districts and everybody knew these were politicians,” Shickler said. “The expectation was they would be drawn by politicians to serve their interests. And that’s what’s that’s gone on throughout most of American history.”

More than two centuries later, he says the same practice that inspired outrage in the nation’s infancy remains one of the most powerful tools in modern politics: empowering elected leaders to choose their voters, rather than the other way around.

RELATED: DOJ prepares to send election monitors to California following requests from state GOPs

Schickler says the practice has gotten worse in recent decades, driven by the nationalization of American politicians and enabled by federal courts.

“It matters a lot less who happens to be the individual representing you, and what matters more is which party has the majority in the House,” he said.

After the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2019 that federal courts could no longer strike down maps for being too partisan, states were effectively left to police themselves.

That ruling is in-part what emboldened states like Texas – which is dominated by a Republican supermajority – to engage in partisan gerrymandering with lesser threat of federal judicial intervention.

Prop 50 will test California’s redistricting legacy

Prop 50 will sunset in 2031, returning California’s map-drawing authorities to the independent commission after the decennial U.S. Census has updated data about voter changes.

Even as a registered Democratic voter, Dai said she fears this one-time change could set a dangerous precedent for politicians to try and eliminate the commission in the future.

Since the redistricting process is enriched in California’s Constitution, lawmakers would have to ask voters again in a statewide proposition to permanently return line-drawing powers back to the Legislature.

Dai said she wants to see the Democratic Party campaign harder to flip California’s districts – which she argues are already competitive because of the independent commission’s work.

“We’re set up, historically anyway, for a blue wave. There’s a good chance we’re going to flip those districts naturally,” she said. “Why give up all the progress that we’ve made to be the gold standard for the rest of the nation on these democratic reforms to cheat when you can win fair and square and not lose your soul in the process?”

California has 52 delegates in the House of Representatives. If approved, Prop 50 would make it easier for Democrats to pick up five of the states nine seats currently held by Republicans.

If you’re on the ABC7 News app, click here to watch live