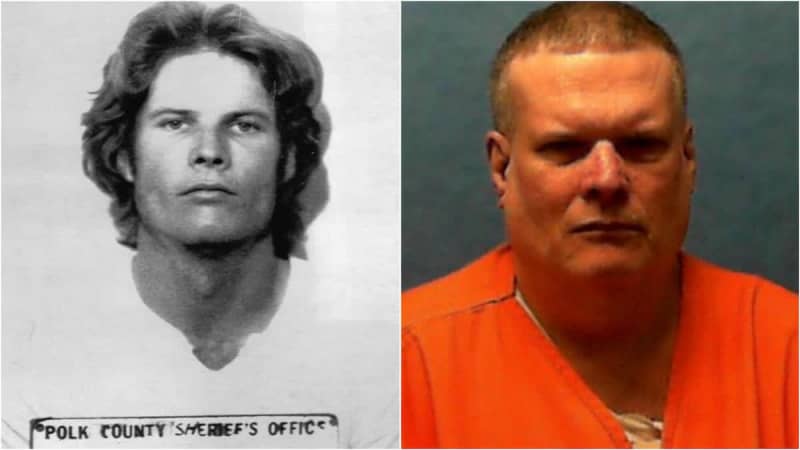

David Joseph Pittman has lived most of his life on Florida’s death row for a 1990 triple murder in Polk County.

He has trouble reading basic words like “dog,” his attorneys say. He often needs to have things explained to him repeatedly. His IQ has throughout his life been pegged in the low 70s.

Evidence going back to his childhood suggests that Pittman, 63, is a man with an intellectual disability, his lawyers say. Federal case law forbids the death penalty for people with intellectual impairments. But Florida plans to execute Pittman next week.

Unless a federal court intervenes, Pittman on Wednesday will become the 12th person put to death in Florida in 2025. Gov. Ron DeSantis has ordered executions at a rapid pace this year, signing more death warrants in any single year than any of his predecessors.

Pittman’s case stands out among the rest. The law and attitudes toward intellectual disability have evolved in the decades since his crime. His attorneys say he should be given a chance to show in court evidence of his impairments, which would now preclude him from capital punishment.

“It is an absolute right that is granted to these people,” attorney Julissa Fontan told a judge in August. “If we do not do this, we are running the risk of actually executing an intellectually disabled man here in the state of Florida.”

The crime that landed Pittman on death row happened in rural Mulberry, east of Plant City. It’s a place known for its phosphate mines and down-home sensibilities. Pittman had never known anywhere else.

A little before 4 a.m. on May 15, 1990, a local resident called 911 and reported his neighbor’s home across a field was engulfed in flames. Mulberry firefighters came and extinguished the blaze. In a search of the cinderblock house, they found in a hallway the bodies of Clarence Knowles, 60, and his wife, Barbara, 50. They found the couple’s daughter, Bonnie, 21, in a bedroom. All three had been stabbed repeatedly. A phone line to the house had been cut.

Investigators focused on Pittman, the estranged husband to the couple’s other daughter, Marie. Amid a contentious divorce and an allegation that he’d raped his wife’s sister, Pittman was said to have made threats to her family.

A witness identified him in a photo lineup as a man she’d seen hours after the killings, running away from a burning car that had been stolen from the crime scene.

His 1991 murder trial featured testimony from jailhouse informants, who claimed he’d made incriminating statements about the murders. A jury found him guilty.

His mother, Frances Pittman, testified in the trial’s sentencing phase that her son didn’t learn to talk until he was 4. She and his stepfather both said Pittman struggled in school and had difficulty controlling his behavior. His challenges spurred teasing from his peers, causing him to act out, his family said. On his first day of first grade, he was sent home for disrupting class.

Despite earning consistent “F” grades, he was socially promoted through eight years of public school in Mulberry and Lakeland, his parents testified.

“To put it simply, he was a child most women would not want to have to raise,” his mother testified. “He was hyper. He just kept your nerves on tight all the time.”

Henry Dee, a Lakeland psychologist, testified that Pittman’s problem wasn’t a lack of intelligence. Dee pegged his IQ at 95, whichis within the range considered average. He acknowledged, though, that Pittman showed signs of brain damage. Years later, lawyers would argue that Dee’s testing method was faulty.

The jury recommended the death penalty for Pittman by a 9-3 vote.

Courts in the early 1990s did not recognize intellectual disability as a bar to execution.

That changed in 2002 with a case called Atkins v. Virginia. In that decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that executing an intellectually disabled person violated the Constitution’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. The 6-3 ruling reasoned that mental and behavioral impairments make people with intellectual disabilities “less morally culpable” and less likely to understand execution as a consequence.

The Florida Supreme Court in 2016 declared that the Atkins ruling applied retroactively. That meant people like Pittman had a chance to have their cases heard in pursuit of a life sentence.

His attorneys sought a full hearing on the issue. Butbefore that could happen, the Florida Supreme Court — which had since become more conservative with the retirement of three longtime justices regarded as liberal — reversed themselves, declaring that the Atkins ruling did not apply retroactively.

DeSantis signed a death warrant Aug. 15, ordering Pittman’s execution. The move triggered an automatic new round of appeals. The sole issue raised by Pittman’s defense centers on his intellectual functioning.

In the years since his trial, further IQ testing and inquiries into his background bolstered the claim that Pittman was intellectually disabled and thus ineligible to be executed.

Testing when Pittman was a child and again after he went to prison pegged his IQ in the low 70s, slightly above the minimum threshold for intellectual disability. His lawyer described Pittman in a recent court hearing as having problems with critical thinking and learning and being “functionally illiterate.”

Lawyers for the state fixated on the one test at the time of Pittman’s trial, which showed a 95 IQ. The average person scores about 100. They acknowledged that the score is an outlier in Pittman’s history. They also argued that Pittman’s defense should have made such claims years ago and thatprocedural rules bar them from raising the issue now.

“He had the opportunity to raise a claim of intellectual disability and he did not,” Assistant Attorney General Timothy Freeland said in the August hearing.

Pittman’s defense responded that he was legally unable to raise such claims. That’s because it took years for courts to settle the retroactivity issue. It was also years before courts recognized that an IQ score alone does not define disability.

“He embraced it at the very first opportunity,” Fontan saidin court. “Unfortunately, while that opportunity was occurring, the Florida Supreme Court decided to reverse itself.”

Pittman’s case has attracted little public attention. But those who study intellectual disability say cases like his deserve special consideration.

Stephen Glicksman, a developmental psychology professor at Yeshiva University and the director of clinical innovation at the Makor Care Services Network, a New York organization that provides support to people with disabilities, said the law should treat people with mental impairments the same way it treats children.

Courts in recent decades have recognized that juvenile brain development makes kids less capable of appreciating consequences.

“If the reason you don’t execute children is because of their cognitive immaturity,” Glicksman said, “then the same standards should apply for people whose cognitive maturity is based on their impairments.”

On Wednesday, the state high court turned down a request to stay Pittman’s execution. A final appeal was filed Thursday with the U.S. Supreme Court.

“I don’t think there is an issue here about whether it is lawful and constitutional to execute him. It’s not,” said Robert Dunham, director of the Death Penalty Policy Project and adjunct professor at Temple University College of Law. “The question in this case is whether Florida intends to flout the Constitution and whether the U.S. Supreme Court is going to let them get away with it.”