The forests that once sheltered the small town of Roseland are turning brown.

A month after a sprawling oil and lubricant facility exploded and rained down slick black droplets all over this predominantly Black town in rural Louisiana, the trees are sick. Federal officials said there’s no threat to human health; however, independent tests recently revealed that inside the goop that coats yards, gardens, and doorsteps is a gallery of 29 chemicals and heavy metals.

Now, many residents are left wondering: Is what was left behind after the Aug. 22 blast safe? If it’s making the trees ill, what about them?

After Smitty’s Supply exploded, over a dozen residents in the town told Capital B they experienced health issues ranging from difficulty breathing to itchy skin. This is all happening while they were physically struggling to clean up in the aftermath of the blast.

Officials from the Environmental Protection Agency, which took over the cleanup process in August, advised residents to remove the black sticky residue themselves. The EPA did not test soil on local properties for contamination. A spokesperson told Capital B that testing was not warranted because they did not believe there was a heavy concentration of toxic chemicals.

But one month later, an independent tester found toxins, including lead, in soil samples as far as six miles from the blast.

And the region’s forests have seen over a 15% decline in their typical greenness, according to ForWarn, a satellite-based monitoring tool. The database is controlled by the federal government to assess when “forest conditions seem unusual or abnormal.” The 15% drop in Roseland is the largest decline possible on the tool’s metric system, but the drop could be larger based on the tool’s fact sheet.

Forestry experts told Capital B that forests lose greenness when contamination and stress disrupt plant photosynthesis, causing leaves to brown, drop, or die as pollutants damage tissues and impair growth. It signals not only a landscape in distress, but a potential threat to every breath nearby, they said.

They also said when fires or chemical disasters devastate vegetation so swiftly, it is often a harbinger of harm to local residents. The same pollutants stunting the growth cycle of trees in the woods, could also work their way into water, soil, and lungs.

That kind of ecological trauma is typically only seen during “major” wildfires, said two retired U.S. Department of Agriculture employees and one private forestry expert, and it clashes with the EPA’s reassurances that there is “no imminent threat to public health.” Wildfire smoke in the U.S. causes measurable harm by triggering respiratory and heart problems, increasing emergency room visits, worsening chronic diseases, and contributing to tens of thousands of premature deaths each year through exposure to air pollution.

For the town’s predominantly Black residents, who are now exposed to the disaster’s chaos and to the uncertainty of the health of their soil, water, and air, the damage could bloom far beyond what eyes or unease can measure. It may be lingering in the trees and the land.

Jimmy Zander looks over a contaminated creek in Roseland. He worries about the impact of the explosion on his aging mother-in-law. (Adam Mahoney/ Capital B)

“We know these chemicals are bad, but we are asking the citizens to do this clean up on their own and put themselves in harm’s way,” said Roseland Mayor Van Showers, who also works at a local chicken processing plant.

In response to inquiries about the surrounding forests’ health, an EPA spokesperson said the Louisiana Department of Agriculture tested soil samples in forested areas and “all results were below levels that necessitate agricultural restrictions.” The agency spokesperson also said it is “important” to note that according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, the region “is abnormally dry.”

However, according to ForWarn, the rest of the region is not experiencing the same forest disruption as Roseland. (The U.S. government will stop funding and operating the ForWarn database on Sept. 30 after 15 years of data modeling.)

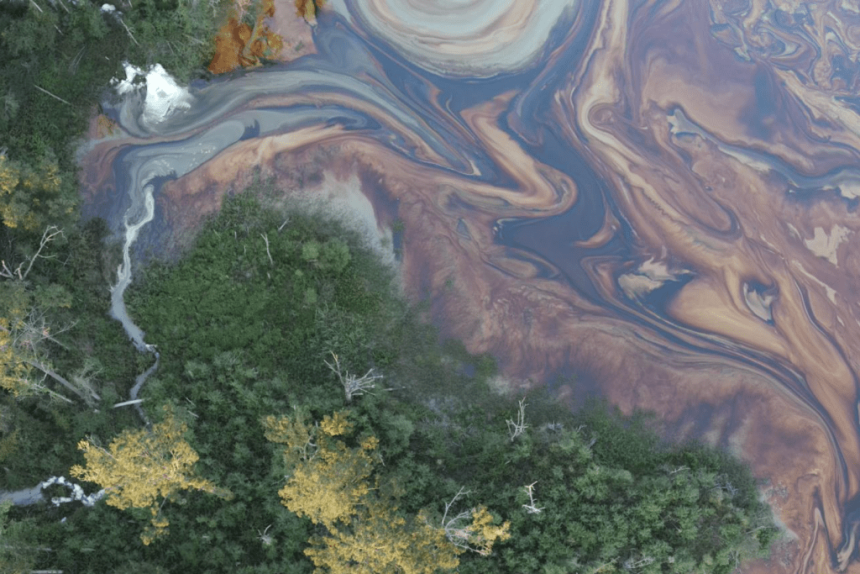

After the August fire, the EPA retrieved samples from local water sources. The agency’s testing detected hazardous substances — such as arsenic, barium, chromium, lead, and nitrobenzene — at levels below the federal threshold. According to the EPA, oil and chemical residues were found in waterways as far as 47 miles downstream. The residue left behind visible slicks in the water like coffee-colored marbled patterns.

But Scott Smith, the independent contamination expert, tested residents’ soil and soot, and found 29 different metals and toxins, including lead. His discovery raises concerns amongst residents about heavy metals and combinations of harmful chemicals in locations where the EPA did not test.

In response, the EPA told Capital B that they “cannot confirm or dispute Mr. Smith’s findings.” In the statement, and multiple other statements, the town was incorrectly called “Rosedale” instead of Roseland.

Councilwoman Wanda McCoy said the state and federal response has shown that “they don’t care about the people of Roseland.”

Dark water samples collected by Scott Smith. (Courtesy of Scott Smith)

“Our kids are playing in this, and no one is helping us clean this up,” said McCoy, who was formerly mayor of Roseland.

“I have experience in decontamination and in removing chemicals because of the field that I work in, but even I’m not going to do it. I’m gonna pay somebody to do it,” Showers said, adding that most residents cannot afford to contract cleanup workers.

The average Roseland resident makes $17,000 annually, and 53% of the town’s residents live in poverty.

Additionally, two-thirds of the town’s population is either under the age of 9 or over the age of 50. By comparison, less than half of Louisiana’s population falls in these categories. These two age groups, according to the EPA, are most at risk for negative health impacts because of pollution.

Showers, the mayor, estimates that most of the town’s elders and more than half of the residents in general are still living with oil streaks on their properties.

“I would like to see the federal or state government do something,” he said. “ It just kind of makes me wonder: had this been a spill somewhere else, what kind of activity would we see from them?” Showers was referencing both the racial makeup of the predominantly Black town and also that it is one of the few largely Democrat-leaning communities in the area. Louisiana’s leadership is majority-white and Republican.

A screenshot of the ForWarn system, highlighting Roseland. ForWarn is a satellite-based monitoring and assessment tool that provides a near-real-time national overview of vegetation greenness to direct attention and resources to locations where forest conditions seem unusual or abnormal.

What ecological harm signals for human health

In the aftermath of the disaster, wildlife across the region has seemed to vanish from the landscape. Residents report that deer and birds, once common, are nowhere to be seen.

Showers, who has cattle and dogs, said his litter of newborn puppies died after the explosion. Farmers who live miles away from the declared disaster zone have said they lost animals and crops to the oily substance that rained down on Aug. 22.

“I can’t let [the cattle] out because I don’t know what is going to happen to them still,” Showers said. “I think that tells us something about our health, too.”

The forests around the town are made up of dense canopies, wetland hollows, and pine and oak trees, and they support the nesting, feeding, and migration for hundreds of animal species. They are part of a network of forests that protect the delicate systems of water and soil that are essential for life in southeastern Louisiana, according to the USDA. But now experts say the forests are weakening and sick.

After disasters like fires and industrial explosions, soot and microscopic bits of dust, oily soot, and ash that slip unseen through the air — also known as particulate matter — can impair tree lungs and immune systems, and it can also impact animals and humans. The combination of particulate matter and lead-contaminated soil can be particularly dangerous because both enter the body through breathing and touch.

What this could mean for Roseland is that, without intervention, the community will be living with uncertainty — and potential risk — for years to come, said residents and advocates. So far, Showers said the EPA’s cleanup has only focused on the site of the explosion and waterways. The agency has set aside $39 million for this work and has already collected 4.7 million gallons of contaminated water.

When toxins like lead, arsenic, and oily chemicals settle into the soil, they can work their way into crops and groundwater. Over time, scientists say, these pollutants could make it harder for plants to grow, as well as increase respiratory and neurological illnesses, and impact childhood development.

In Roseland, most families rely on their gardens, animals, and local water to sustain them. Many residents said for them, the stakes are even higher. Every garden harvest, each trip to the local creeks, and every day spent outside carries a new layer of worry, they said.

Retired Lt. Gen. Russel Honoré, who gained national recognition during Hurricane Katrina recovery efforts, visited Roseland this month, and called for more federal support.

“They are trying to handle this like it’s a normal emergency,” said Honoré, who is also calling for free blood testing for residents to check for toxins. “It’s not a normal emergency.”

Earlier this month, the Louisiana Environmental Action Network filed an intent to sue the EPA for its response to the disaster.

“This explosion was not an accident,” wrote LaCrisha McAllister, an attorney representing some Roseland residents, in a statement to Capital B. “It was the foreseeable result of years of negligence, and the surrounding community is now left to deal with the fallout.”

Read More:

The post In This Black Louisiana Town, Forests are Browning and Animals are Dying appeared first on Capital B News.