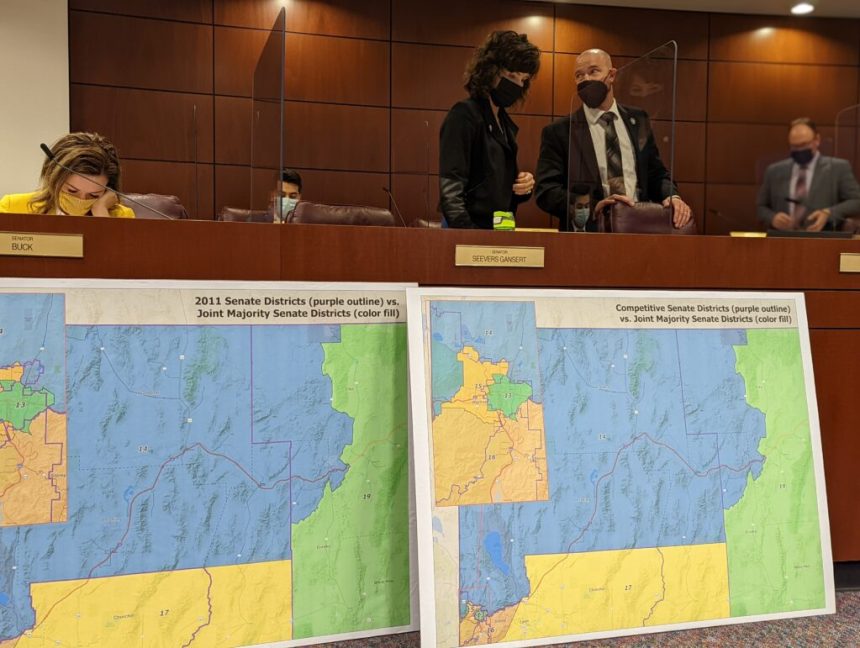

Lawmakers after a joint committee on redistricting in 2021. (Photo: April Corbin Girnus/Nevada Current)

Hoping to capitalize on public interest in, and outrage over, partisan gerrymandering, a grassroots group of Nevadans has filed a proposed ballot measure to establish an independent redistricting commission and prohibit mid-cycle redistricting.

The group, Vote Nevada PAC, also filed a second proposed ballot question to amend the state’s Voter Bill of Rights to include a provision that could force the two major political parties to open their primaries.

Both petitions were filed with the Nevada Secretary of State’s Office on Tuesday, according to members of the political action committee. Both proposals involve amending the Nevada State Constitution, meaning if they qualify for the ballot, they will have to be approved by voters twice in subsequent elections — 2026 and 2028.

Sondra Cosgrove and Doug Goodman, both longtime advocates for statewide election reform in the Silver State, are behind the efforts. Joining their cause this election cycle is former state Assemblymember Claire (Clara) Thomas, who since leaving office in 2024 has left the Democratic party and registered as a nonpartisan.

The independent redistricting commission proposed by Vote Nevada would be composed of a mix of Democrats, Republicans, and non-major-party voters, reflecting active voter registration splits in the state.

Currently in Nevada, redistricting — that is, the redrawing of the political district boundary lines in order to even out respective populations as regions grow or shrink — is the purview of the Nevada State Legislature, where lawmakers are, with minimal exceptions, able to draw new maps for their own political gain. The governor can veto the maps.

It is an “indefensible, corrupt process that must change,” argues Vote Nevada.

Nonpartisan and third-party voters comprise 43% of the 2.1 million active registered voters as of August 2025, according to the Nevada Secretary of State’s Office.

The proposed ballot question would limit redistricting to the 180 days following the release of the U.S. Census, essentially barring mid-cycle redistricting efforts like those recently undertaken by the Republican-controlled Texas State Legislature.

Cosgrove believes the blatant political gerrymandering in Texas has brought unprecedented interest in redistricting across the country, making it an ideal time to discuss the issue in Nevada.

In previous years, pitching the independent redistricting commission ballot measure to voters involved a lot of explaining, she said, but right now “it’s not hard to say we want to get rid of gerrymandering in Nevada.”

She continued, “People are at least aware that it’s a thing that’s happening and it’s probably bad. It’ll be easier to educate the public now because it’s in the news everywhere.”

Vote Nevada filed proposed ballot measures to form an independent redistricting commission — in 2020, 2022, and 2024. All three efforts failed to make it in front of voters, either because opponents successfully challenged it in court or because they failed to gather enough signatures to qualify for the ballot.

In 2024, under the name Fair Maps Nevada, two nearly identical ballot measures to form independent redistricting commissions were deemed “legally deficient” by the Nevada Supreme Court because they did not establish a revenue source to pay for the new body they created.

Cosgrove disagrees with the ruling but in an attempt to address it, the new measure transfers existing funding for redistricting from the legislative process to the independent redistricting commission.

After the filing of a proposed ballot measure, there is a 15-day window for legal challenges. Those legal challenges, which go before a district court and often to the Nevada Supreme Court on appeal, can be a death sentence for proposals, either directly through an unfavorable ruling or indirectly by sucking up time and resources.

The Vote Nevada PAC, in a lengthy brief on the history of efforts to form a commission, urged both major political parties to forgo a legal challenge this time around.

The language of the bill has survived the standard legal challenge just five years ago, they point out. The language was also considered by the nonpartisan Legislative Counsel Bureau earlier this year when Republican state Sen. Ira Hansen sponsored the proposal as a piece of legislation. (Democrats did not give that resolution a hearing.)

It has been thoroughly vetted, the organizers argue, and the political parties should “let the people debate this idea and then cast their votes, as is their right in the Nevada Constitution.”

“I am daring them to sue me,” Cosgrove told the Current. “Sue me and I’m going to spend this whole election cycle ripping them to shreds.”

Cosgrove said she’d be happy to point out to voters that Democrats oppose creating an independent redistricting commission in Nevada where they are the majority party but support creating one in Ohio where they are the minority party.

Similarly, Republicans in Nevada are more supportive of the proposal while their counterparts in red states are opposed.

Thomas, the former Democratic assemblymember, says the leaders of her former party should consider the possibility they might one day find themselves reckoning with a Republican trifecta in Carson City.

“I keep saying that the pendulum is getting ready to swing in a different way,” she said. “Republicans stand a great chance in taking over the leadership. And when that happens they will want to do redistricting, and it will not fare well for the communities that I see.”

In 2021, Democrats controlled the legislature and governor’s mansion and passed a series of new maps that were widely criticized by Republicans, progressive groups, and election advocates.

Thomas’ two terms in the Assembly included that 5-day redistricting special session.

She said the lack of transparency criticized by Republicans and observers also extended into the chambers themselves. Assemblymembers like herself, who did not hold a leadership position, had no say in the process. They were simply expected to show up and vote with what leadership presented.

“We didn’t know anything about how they were divvying up the communities until they divided it up,” she said. “Then it was, ‘This is what it is.’”

Thomas ultimately voted for the maps, as did all Democrats except one, then-Assemblymember (now state Sen.) Edgar Flores. But now she is hoping the process can be changed to get closer to the people.

Vote Nevada doesn’t have deep financial pockets to fight legal battles or pay signature-gathering companies. “We have $0,” Cosgrove acknowledged. But the PAC is hoping the moment is right for a grassroots movement to form.

Voter Bill of Rights amendment

Vote Nevada’s second ballot measure would amend the Voter Bill of Rights, which was enshrined in the state constitution in 2020.

The proposed ballot measure would add that all eligible voters have a right “to fully participate in all publicly funded elections without limitation, including, but not limited to, any requirement to affiliate with any private organization, such as a political party.”

The ballot measure would upend the state’s presidential preference primaries, which are publicly funded but only open to voters who register with either of the two major political parties.

Vote Nevada notes that the political parties would be free to engage in privately funded nominating processes. The Nevada Republican Party last year did just that despite the state mandating a presidential preference primary be held. (That split resulted in “none of these candidates” winning the nonbinding state-run primary and Donald Trump winning the party-run caucus.)

Cosgrove and Goodman have long argued that the growing number of nonpartisan voters are being disenfranchised because they cannot participate in primaries, which are often competitive and sometimes decide the general election.

The duo was heavily involved in 2022 and 2024’s Question 3, which proposed a ranked choice voting and open primary election system. The proposal passed in 2022 but failed to pass in 2024. It faced fierce opposition from both major parties.

Many opponents of that measure suggested they were okay with open primaries and that the problem lay with using ranked choice.

During this year’s legislative session, Assembly Speaker Steve Yeager acknowledged those frustrations. He sponsored a bill to allow nonpartisan voters to participate in either Republican or Democratic non-presidential primaries. The bill passed the Legislature but was vetoed by Republican Gov. Joe Lombardo.

When pitching the legislation, Yeager told his peers he feels the dam to open primaries is “going to break one way or another.”

Thomas leaves Democratic party

Thomas described making the decision to register as nonpartisan as “hard pressed.” She had been a loyal Democrat her whole life but became “disenchanted” by what she sees as the party’s lack of leadership and prioritization of lobbyists and special interests.

“It is not the party that my parents taught me about,” she said. “It’s not the party that I grew up with in Nevada.”

Thomas said the decision was not a direct response to the Nevada Senate Democratic Caucus endorsing her competitor last year for the state Senate District 1 Democratic primary, though she acknowledged there was conflict.

“Did I appreciate the leadership telling lobbyists not to support me? And (saying) if they do support me that their bills would not be heard? Those are tactics that I think we see in the Republican party. Never did I think the Democratic party would do that. But they did.”

Thomas lost the Democratic primary in June last year to Michelee Cruz-Crawford, who would go on to win the general election in the solid blue district. Thomas said she didn’t decide to leave the party until later, following a “really thoughtful process” about where the party was headed.