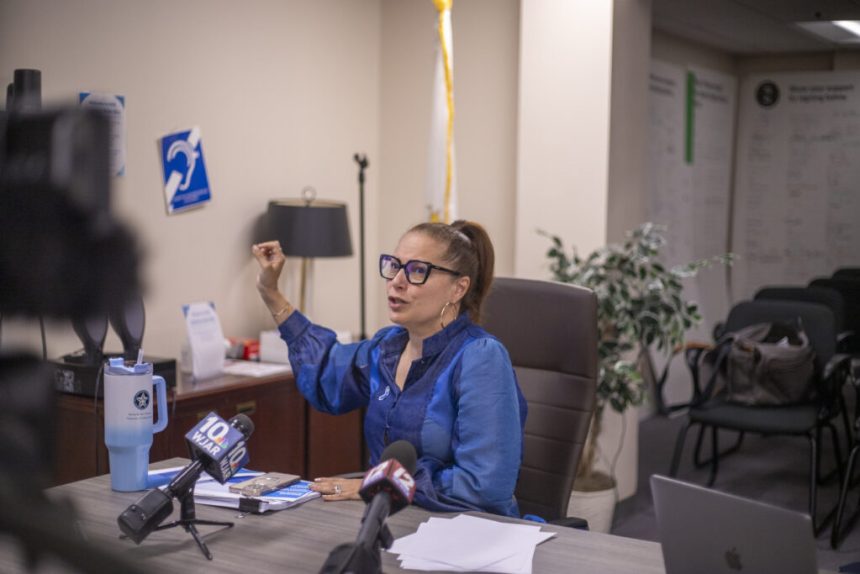

Rhode Island Education Commissioner Angélica Infante-Green discusses 2025 Rhode Island Comprehensive Assessment System standardized test results during a media briefing on Oct. 1, 2025. (Photo by Alexander Castro/Rhode Island Current)

Rhode Island students’ standardized test scores moved up this year, outpacing pre-pandemic proficiency in math.

Of the more than 58,000 students in grades 3-8 who took the annual Rhode Island Comprehensive Assessment System (RICAS), 31.4% were proficient in math, according to the 2025 results released Thursday. That’s up from last year’s 30.1% as well as the 29.8% observed in the 2018-2019 school year.

English Language Arts proficiency, however, remains harder to budge, with 33.7% of students meeting the state benchmark, compared to 38.5% in the 2018-2019 school year, the year used as a baseline comparison. It is still an improvement over last year, when 30.8% of students were proficient.

The results, released Thursday morning by the Rhode Island Department of Education (RIDE), show modest improvement and continuing reversal of pandemic-era learning declines on the RICAS. Speaking to reporters Wednesday ahead of the scores’ public release, state education Commissioner Angélica Infante-Green emphasized the “good news” hiding in the numbers.

“I want to be clear, we’re nowhere close to where we want to be, but we are heading in the right direction,” Infante-Green said. “The reality is that no one is nationwide, but Rhode Island’s momentum is real and measurable.”

The assessments involve multiple choice questions, short written answers, and a few multi-step problems. The test is cloned from Massachusetts’ Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS), giving RIDE a way to compare the neighboring and often rivalrous states.

This year, the gap between the Ocean and Bay states has narrowed to about 9.3 percentage points in math and 8 percentage points in English Language Arts. If the entire state of Rhode Island were treated as a Massachusetts district, it would fall around the 30th percentile — up from the bottom decile in 2018.

“I think Massachusetts needs to watch out,” Infante-Green told reporters.

This year’s MCAS results showed about 42% of Massachusetts students in grades 3-8 were proficient in English Language Arts and 41% were proficient in math. The shrinking gap, however, also owes partly to Massachusetts’ own declines since 2019.

Meeting or exceeding Massachusetts’ assessment numbers by 2030 is part of Gov. Dan McKee’s plan for the decade’s remaining years, a goal RIDE reiterated this year. When asked by reporters if the benchmark is the Bay State’s current, lower numbers, or the higher, pre-pandemic numbers, Infante-Green parried.

“They’re still one of the top states in the nation. … Even though they’re dropping, what we’re doing is moving up,” she said.

The gap has shrunk by more than half since the 2018 RICAS, when Massachusetts and Rhode Island were separated by gaps of 17 percentage points in English and 20 percentage points in Math.

As for high school assessments, they were mixed: 51.6% of juniors met the SAT benchmark in reading and writing, up from 47.8% last year and slightly above 2019’s 50.5%.

In Math, 23.3% of juniors met the standard, up from 21.7% in 2024 but still below 2019’s 31.2%.

The SAT’s benchmark scores, which are formulated by College Board and used to determine college readiness, are 480 on reading and writing and 530 on math.

Reducing absenteeism has been a cornerstone of McKee and Infante-Green’s educational policy. Across RICAS, PSAT and SAT scores, students who are not chronically absent score between 18 and nearly 24 percentage points higher on tests than their chronically absent peers.

“If parents are hearing me, this is why it matters,” Infante-Green said to the TV news’ cameras.

The commissioner also stressed that multilingual learners are excelling, which she attributes to spillover benefits of the training received by teachers specializing in multilingual teaching. This year’s RICAS data shows multilingual learners’ proficiency has risen since 2019 in English Language Arts by 5.7 percentage points and in math by 8.8 percentage points. Students who recently completed programs designed for multilingual learners are above the state average, with 42.4% proficiency in English Language Arts and around 39% proficiency in math on this year’s RICAS.

The school library at Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Elementary School on the East Side of Providence. (Photo by Alexander Castro/Rhode Island Current)

Mississippi or Massachusetts?

Infante-Green assumed her post at the education department in April 2019, roughly 11 months before the COVID-19 global pandemic, an unenviable time to be freshly charged with responsibility for Rhode Island’s more than 135,000 public school students. The pandemic’s consequences, especially its outsized influence on absenteeism rates, linger on in the state’s classrooms, Infante-Green said.

“I met with elementary school principals yesterday who said that they have kids coming into kindergarten wearing pull ups,” Infante-Green said. “It’s a different world right now.”

Infante-Green is not alone in her uphill climb. While the Rhode Island and Massachusetts tests are duplicates, most state-level assessments differ, making direct comparisons shaky. The National Assessment of Educational Progress, also known as the Nation’s Report Card, is a more apples-to-apples approach from the federal government which looks at proficiency in math and English for fourth- and eighth-graders.

Across the nation, proficiency levels are routinely below 50% in both language and math, even in Massachusetts’s top-performing scores on the 2024 national assessment: 40% in fourth- and eighth-grade reading, and 51% and 37% in fourth and eighth grade math, respectively.

Rhode Island sat near national averages on the 2024 national assessment, with eighth grade reading at 30% and eighth grade math at 26% proficiency. For fourth graders, those numbers were 33% on reading and 38% on math.

Infante-Green mentioned the Mississippi Miracle — the nickname given to a series of educational reforms in Mississippi over the last decade. On Mississippi’s own state tests for 2025, 47.4% of students were proficient or above in English and 54.5% in math. (On the national test, these gains were strongest in fourth grade, with eighth graders performing nearer the middle of the national pack.)

“Mississippi didn’t go to the top, but they moved from the bottom nationally to the middle, and they kept moving up,” Infante-Green said. “It took 10 years for them to do that after they got everybody trained.”

Kelsey Piper writes in a recent analysis for The Argument, a policy-focused media outlet, that these reforms have benefitted students despite underlying wealth disparity: “Black students are as likely to be basic-or-above readers in Mississippi (where the median Black household income was $37,900 in 2023) as in national top performer Massachusetts (where the median Black household income was $67,000 in 2022.)”

The Mississippi model owes much to a rejection of a literacy approach known as whole language. The now discredited model eschewed phonics instruction in favor of an assumption that kids learned languages naturally. Even as recently as 2022, reading curricula at least partly based in whole language approaches — like Lucy Calkin’s “Units of Study,” which the author has since revised to incorporate more phonics — were in use by about 16% of kindergarten to grade two teachers nationwide.

Infante-Green balked when asked if whole language instruction was anywhere near Rhode Island’s reading curriculum. Since 2019, the state’s Right to Read Act has required that educators be trained in teaching methods based in the science of reading, which restores phonics to a place of high importance.

A slide from a Rhode Island Department of Education 2024 presentation shows examples of books which demonstrate a “structured” approach to literacy, the state’s preferred method. (Rhode Island Department of Education)

“We decided to do this during the pandemic, while other states were shut down,” Infante-Green said of the state’s efforts to ground its literacy curriculum in the science of reading.” “This is the year where most of the teachers will be trained.”

She told reporters that even Massachusetts has asked about its neighbor’s approach to teaching literacy.

“They’re actually looking at what we did with the science of reading,” Infante-Green said, adding that she expects to continue the conversation with the commonwealth’s new education commissioner, who began working in July.

In 2019, RIDE received a federal Comprehensive Literacy State Development grant worth $20 million to fund its literacy curriculum, coaching, and training in the state’s schools. RIDE received a similar grant worth $40 million in 2024.

By November 2024, RIDE data showed about 80% of educators met the proficiency standard for training in science of reading-based methods, which prioritize “decodable texts” and “phonics patterns,” according to a RIDE presentation.

The commissioner gave the ambiguity of the letter “y” as an argument for precise training. “Y” is a vowel, but usually only at the end of a syllable or word. Still, kids were often taught it’s “sometimes” a vowel, which Infante-Green said can be unclear and leads to confusion for students.

Infante-Green added that English is not known as a language of simplicity, noting that the letter “e” can be pronounced more than a dozen ways.

“Only English is that complicated,” Infante-Green said.

SUBSCRIBE: GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX