The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

a bright line runs through Iran’s domestic movement for democratic change: on one side, frank opponents of the regime, and on the other, proponents of incremental reform. One figure stands out for bridging that divide, making him one of Iran’s most promising political prospects.

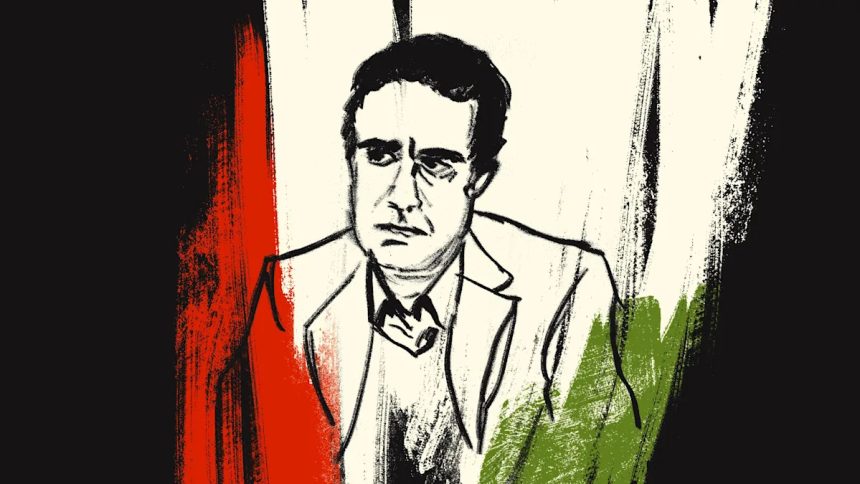

Mostafa Tajzadeh, a former deputy interior minister, is one of Iran’s best-known and most broadly popular political prisoners. Tajzadeh had already spent more than a decade behind bars, much of it in solitary confinement, when the Iranian judiciary handed him a new five-year sentence, on July 12, for charges based on statements he’d made in captivity. His release date is now set for 2032.

Tajzadeh supports free elections, opposes mandatory veiling for women and other repressive policies, and backs diplomatic rapprochement with the United States. Abdollah Momeni, an activist and former political prisoner, described Tajzadeh to me as having “a rare combination of moral courage, political honesty, and loyalty to the people. He is respected both by official reformists and a significant section of civil society, radical democracy activists, and antiauthoritarians.”

[Read: The Iranian dissident asking simple questions]

Reform in Iran has meant working inside the system to improve it, and many of its practitioners therefore refuse to endorse street protests that voice criticisms of the regime as a whole. Tajzadeh is different. He lent his explicit support to the 2022–23 movement known by the slogan “Women, Life, Freedom.” He has also called for abolishing the position of supreme leader, which would effectively end the Islamic Republic. But he’s still a reformist in other ways: He opposes violently overthrowing the regime, and even ran for president in 2021 as the main candidate of the reformist camp until he was denied a place on the ballot. (Wholesale opponents of the regime often reject participating in such elections at all, on the grounds that they provide democratic window dressing for an autocratic system.)

In June, Israeli air strikes pummeled Iranian targets, and Tajzadeh issued a statement from prison both condemning the bombardment and acknowledging that some Iranians were happy about it. He called for a “peaceful transition to democracy” by means of a constituent assembly and a change in the constitution. On July 23, he called on Ayatollah Ali Khamenei to either agree to free elections and “fundamental changes” or resign.

That Tajzadeh’s appeal bridges Iran’s fractious opposition was evident in the reaction to his most recent sentencing. Many in the opposition, including in the diaspora, spoke out against it. So did Azar Mansouri, the head of the Iranian Reformist Front, a coalition of reformist groups and political parties, who told me that she opposes Tajzadeh’s imprisonment because he “has a long history of trying to bring about change from within the system; he has never backed violence; and his activities have been mostly civic, political, and peaceful.” Alan Ekbatani, a California-based antiregime activist and former political prisoner, told me that he had “high hopes” for Tajzadeh, “especially if he dares to declare solidarity with those who are after fundamental transformation and separation of religion from politics,” because “he has resisted Khamenei and has shown he is ready to pay a cost in the pursuit of his goals.”

Tajzadeh served his first prison sentence from 2010 through 2016. Upon release, he organized a series of online debates on platforms such as YouTube and Clubhouse. Before tens of thousands of Iranians, Tajzadeh engaged figures as diverse as Tehran’s hard-line mayor, Alireza Zakani, and Morad Veisi, a well-known supporter of Iran’s former crown prince, Reza Pahlavi. He even declared his readiness to debate Pahlavi himself—a major taboo for a former regime official—shortly before he was sent back to prison, in 2022.

This insistence on engaging a wide range of Iranians in conversation was what drew Saeed Barzin, a United Kingdom–based dissident, to write a two-volume book in Persian about Tajzadeh. Barzin told me that Tajzadeh is “unique in modern Iranian history as someone who encourages adversarial political tribes to maintain a dialogue with each other. This is crucial for Iran’s plural society.”

Tajzadeh entered politics as a revolutionary activist in 1979 and served the regime in the 1980s in a variety of positions, mostly within the Ministry of Culture. At the time, Mohammad Khatami headed that ministry. And much like Khatami, in the 1990s, Tajzadeh began to temper his revolutionary Islamism with an openness to liberal and democratic reform. Khatami won the presidency on a reformist platform in 1997 and initially considered Tajzadeh for his chief of staff before making him deputy interior minister. This position placed Tajzadeh on the front lines of the battle over democratization that unfolded between Khatami’s government and the hard-line establishment that eventually defeated it.

The Khatami government sought to curb the abuses of the Iranian security establishment, secure greater freedoms of speech and association, create space for a more robust civil society, and make directly elected local councils laboratories for democratic change. Most of these initiatives met obdurate resistance from more powerful sectors of the state, and by the end of Khatami’s second term, in 2005, the reform movement had lost much of its momentum. A hard-line president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, succeeded Khatami. But when his first term came to an end, Ahmadinejad faced a new reformist challenger, who revived Khatami’s energy and then some: Mir Hossein Mousavi, a former prime minister, whose supporters called themselves the “Green Wave” in 2009.

Ahmadinejad quickly declared himself the winner of that election, and Mousavi claimed that the results were rigged. A street movement broke out in Mousavi’s support. The regime crushed the protests and placed Mousavi under house arrest. It also banned the main reformist parties and meted out long prison sentences to the politicians associated with them, including Tajzadeh. When these men came out of prison, they mostly chose between two paths: Some left Iran to become critics in exile; others remained inside and kept their heads down, not daring to disparage Khamenei, in the hopes that they might find their way back into politics.

Tajzadeh is notable for having chosen a third path. He has remained in the country but articulated a radical critique of the Islamic Republic, openly assailing Khamenei for “violating the rights, dignity, and freedom of Iranians” and calling for the leader’s position to be abolished. Whether by design or merely by following his conscience, Tajzadeh has put himself in a position to unite the agendas of Iranian dissidents inside and outside the country.

“He doesn’t like to be talked about as a leader, hero, or savior,” Tajzadeh’s wife, Fakhrolsadat Mohtashamipour, told me, employing a Persian mode of modesty. “All he does is for the country and for his compatriots and against authoritarianism.”

Mohtashamipour married Tajzadeh in 1980, shortly after the revolution, and she told me that theirs has always been a political partnership. “We are still fighting for the ideals of 1979, which have now been tarnished under a dictatorship that tolerates no criticism,” she said. “The regime is afraid of him because they know he can attract people by his words. Although keeping him in prison also shows their absolute stupidity, because he has become even more a point of reference from inside prison.”

[Arash Azizi: The Islamic Republic was never inevitable]

The notion that Iranian reformists see their project as continuous with the ideals of 1979 has helped make them a credible force inside the regime, but it has also made some younger activists uneasy. Faraj Sarkohi, a dissident writer in exile, told me that the revolutionary and Islamist pasts of people such as Tajzadeh and Mousavi could present obstacles to winning the trust of secular Iranians today. “Tajzadeh can’t be a leader for the transition,” Sarkohi said, suggesting that “workers, women, students, and pro-democracy intellectuals” would be likelier candidates for that role. “But he can be part of a movement for democracy and help convince some of the regime base and bring them on this path.”

From another point of view, that very trajectory—from Islamist revolutionary to champion of the people’s democratic aspirations—carries a particular moral weight. Mousavi, who is 83 years old and has been under house arrest since 2011, recently called for a constituent assembly—a call he also made in support of the street protests in 2022. Mousavi was Iran’s prime minister in the 1980s, when he was a favorite of the regime’s founder, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Now he is too frail to serve in a major political role himself, but more than 800 prominent Iranians inside and outside the country have signed a petition in support of his call for a constituent assembly. Tajzadeh and Momeni are among those signatories (Momeni has already been summoned for questioning by the judiciary as a result). Another demand for a constituent assembly “to be organized under the supervision of independent international institutions” has been issued by a more radical group of dissidents that includes the Nobel Peace laureate Narges Mohammadi, the human-rights activist Nasrin Sotoudeh, and more than 1,500 other Iranians.

Outside Iran, the opposition can seem bitterly divided, with some parts of the diaspora embracing Pahlavi’s leadership and others in disarray. But a political space appears to exist inside the country for critics who wish for a different kind of government from the Islamic Republic, and who may look to figures such as Tajzadeh for the wisdom and moral courage to make it real.