LOS ANGELES (AP) — The midterm elections might be a year away, but the fight for control of the U.S. House is underway in California.

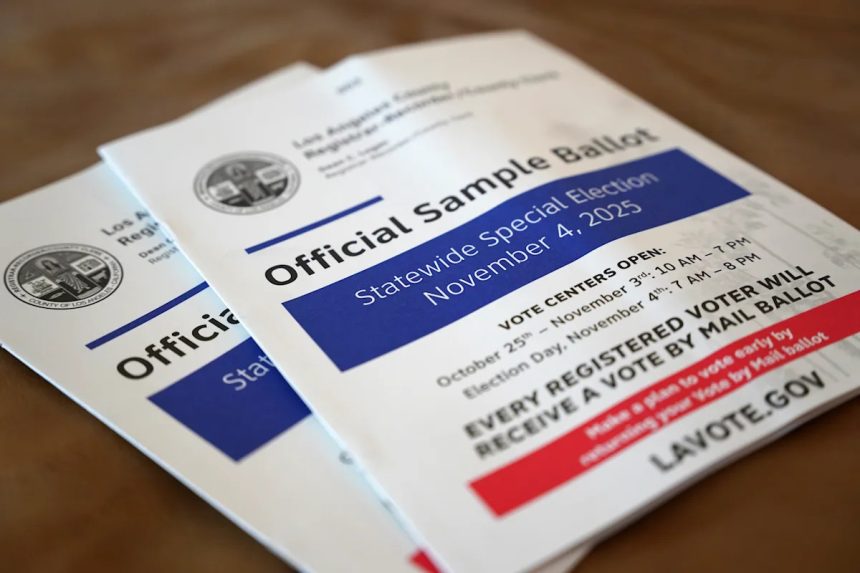

Voting opened statewide Monday on whether to dramatically reshape California’s congressional districts to add as many as five Democrat-held seats in Congress — a possible offset to President Donald Trump’s moves in Texas and elsewhere to help Republicans in the 2026 election.

The outcome of the 70-word, “yes” or “no” question could determine which party wins control of the closely divided House, and whether Democrats will be able to blunt Trump’s power in the second half of his term on issues from immigration to reproductive rights.

The proposal is “a starting point for the 2026 race,” said Democratic consultant Roger Salazar.

“2026 is the whole ball game,” he said.

The national implications of California’s ballot measure are clear in both the money it has attracted and the figures getting involved. Tens of millions of dollars are flowing into the race — including a $5 million donation to opponents from the Congressional Leadership Fund, the super PAC tied to House Speaker Mike Johnson. Former action-movie star and Republican Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger has spoken out to oppose it, while former President Barack Obama is in favor, calling it a “smart” approach to counter Republican maneuverings aimed at safeguarding House control.

The election that concludes Nov. 4 will also color the emerging 2028 presidential contest in which Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom — the face of the campaign for the new, jiggered districts — is widely seen as a likely contender.

So goes California, so goes the nation?

“Heaven help us if we lose,” Newsom wrote in a recent fundraising pitch to supporters. “This is an all-hands-on-deck moment for Democrats.”

An election gamble that could check Trump’s power

The unusual special election amounts to a Democratic gambit to blunt Trump’s attempt in Texas to gain five Republican districts ahead of the midterms, a move intended to pad the GOP’s tenuous grip on the House.

The duel between the nation’s two most populous states has spread nationally, with Missouri redrawing House maps that are crafted state by state. Other states could soon follow, while the dispute also has become entangled in the courts.

A major question mark has emerged in Texas, where a panel of federal judges is considering whether the state can use a redrawn congressional map that boosts Republicans.

If the Texas map is blocked even temporarily, it’s not clear how that decision would influence California — if at all — where voting is underway. Newsom has previously indicated that California could keep its current map if other states pull back efforts to remake districts for partisan advantage, but that language was not included in the final version of what’s officially known as Proposition 50.

GOP could be left with just four House seats in California

If approved in California, it’s possible the new political map could slash five Republican-held House seats while bolstering Democratic incumbents in other battleground districts. That could boost the Democratic margin to 48 of California’s 52 congressional seats, up from the 43 seats the party now holds.

Liberal-tilting California has long been a quirk in House elections — the state is heavily Democratic but also is home to a string of some of the most hotly contested congressional districts in the country, a rarity at a time when truly competitive House elections have been dwindling in number across the U.S.

The contours of the race have taken shape, with Newsom framing the contest as a battle to save democracy against all things Trump, while Republicans and their supporters decry the proposal as a blatant power grab intended to make the state’s dominant Democrats even more powerful while discarding House maps developed by an independent commission. Democrats crafted the proposed lines behind closed doors.

Republicans hold a 219-213 majority in the U.S. House, with three vacancies.

New maps are typically drawn once a decade after the census is conducted. Many states, including Texas, give legislators the power to draw maps. California is among states that rely on an independent commission that is supposed to be nonpartisan — the Democratic ballot proposal would shelve that group’s work and postpone its operation until the next census.

Creative boundary lines create districts to favor Democrats

In some cases, the recast districts would slice across California, in one case uniting rural, conservative-leaning northern California with Marin County, a famously liberal coastal stronghold north of San Francisco. In others, district lines are left unchanged or have only minor adjustments.

With rural and farming areas in some cases being combined in new districts with populous cities, there is “worry about us losing our voice,” said John Chandler, a partner in almond-and-peach grower Chandler Farms in the state’s Central Valley farm belt. “It hurts us,” Chandler said during an online event organized by proposition opponents.

Who will show up and vote?

Democrats come to the contest with significant advantages — they outnumber registered Republicans in the state by a nearly 2-to-1 margin, and a Republican candidate hasn’t won a statewide election in nearly two decades.

Still, ballot questions can be unpredictable. Voters are in a grumpy mood nationally and hold mixed views of both political parties.

It’s difficult to determine precisely who might show up in an election with no candidate on the statewide ballot — only a question involving a constitutional amendment on the arcane subject of redistricting, or the realignment of House district boundaries. And campaigns are competing for attention in a nation of nonstop distraction, from wars abroad to the political stalemate in Washington.

Supporters and opponents are running a cascade of ads in the state’s big media markets. Trump is trying to “steal congressional seats and rig the 2026 election,” one ad from supporters warns. Opponents are spotlighting a recent appearance by Schwarzenegger, who in one ad clenches his fist and says, “Democracy — we’ve got to protect it and we’ve got to go and fight for it.”

In the state’s Central Valley, Kelsey Hinton is working to mobilize infrequent Latino voters hitched to hectic jobs and child care who are often overlooked by major campaigns. Her group, the Community Water Center Action Fund, dispatches canvassers to knock on doors to explain the stakes in the election.

Operating separately from Newsom’s campaign, and backed by funding from a left-leaning political group known as the Progressive Era Issues Committee, they hope to boost voter participation in an area where turnout can be among the sparsest in the state.

What are they finding? “People don’t even know there is an election,” Hinton said.