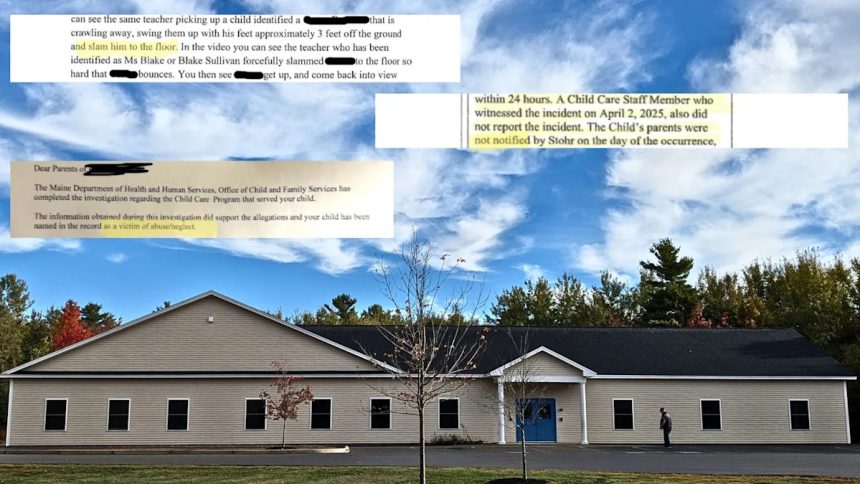

On April 2, a teacher at a Brewer child care center picked up a young boy who had crawled away, swung him until his feet were about three feet off the ground and slammed his bottom onto the floor so hard he bounced, according to video footage.

A speech therapist working at the daycare described the 3-year-old’s scream as “blood curdling,” and would later tell police the child cried and said he was hurt for another five to 10 minutes.

The daycare, Elevate Child Care Center, did not tell the boy’s parents what had happened despite state regulations requiring licensed providers to immediately inform parents or guardians of any serious injury or incident involving their child.

It wasn’t until May 6, more than a month later, that the boy’s mother, Kristen Boucher of Brewer, received a phone call from the Maine Department of Health and Human Services alerting her that it had been investigating her son’s teacher, Blake Sullivan of Carmel, for abuse. The call would become part of a chain of events that led to the large daycare’s closure last month.

“I was in complete shock,” Boucher told The Maine Monitor. “As a parent, your greatest responsibility is keeping your child safe, and to hear that an adult entrusted with his care physically harmed him was devastating.”

The case at Elevate is not the only one in which a child care provider failed to tell parents or the state about serious incidents despite being required to under Maine’s licensing rules.

Between January 2021 and July 2024, the state cited 60 child care providers for failing to tell the state or parents within the required timeframe — or at all — about a range of violations, including rough handling, unsupervised children and cruel discipline, according to thousands of publicly available inspection reports reviewed by The Monitor.

Twenty-three providers were cited twice, and 11 were cited three or more times for not disclosing violations.

There are more than 1,500 child care providers in Maine, so the percentage that failed to report violations is small. Gaining a true picture of their lack of disclosure, however, is difficult when child care center leaders are largely responsible for reporting themselves. The records show how difficult it can be to hold them accountable.

“We are looking for certainty in terms of children being safe. And that is more challenging than we’d like it to be,” said Melissa Hackett, a policy associate at the Maine Children’s Alliance.

In one instance, a child at a child care center in Ellsworth was left alone outside on a playground for an hour and 15 minutes. At a facility in Belfast, child care staff members didn’t know a child was missing until someone who didn’t work at the center found the child in a ditch by the road. At a Lewiston daycare center, a staff member consistently grabbed children by one arm, dragged them into another room and then slammed the children onto the floor or their cot, leaving marks where they had been grabbed.

None of the incidents were reported as required. Instead they came to light indirectly, such as when inspectors visited a facility for a different reason and interviewed staff members, or they received a complaint from a parent or other staff member, according to state inspection reports.

In addition to notifying a child’s parent or guardian immediately of any serious injury or incident involving their child, state regulations require licensed child care providers to document what happened in the child’s record that day. A parent or guardian must then review and sign the document within two business days.

Child care providers must also report any suspected abuse or neglect immediately to the state’s child protective intake phone line. Then they must notify the child care licensing unit within DHHS within 24 hours of any child abuse and neglect allegations involving a child care staff member.

The two women who ran Elevate in Brewer, Sara Grant and Merissa Stohr, did none of these things, even though the speech therapist told Stohr what had happened that day, April 2, according to DHHS’ summary of the center’s violations and other records shared by Boucher.

A teacher who witnessed the incident also did not report it. It was the second time in less than six months that Elevate’s leaders did not report concerning conduct as they were required to do.

Instead the speech therapist — who didn’t know the boy but saw Sullivan grab him roughly from behind and drop him to the ground — decided to call the child protective line herself, sparking the outside investigation.

The same day that Boucher spoke with DHHS, on May 6, she and her husband pulled their son from Elevate and then went to the Brewer Police Department to report the teacher.

When police interviewed her, Sullivan said that she did not remember putting the boy down so hard, according to the police report. In letters that Sullivan sent to the daycare and the child’s family, she described how she “let a moment of frustration cause me to make a choice I cannot take back,” police noted. She was charged with assault, endangering the welfare of a child and reckless conduct.

Sullivan’s attorney, Jeff Silverstein, declined an interview request from The Monitor. Sullivan’s court case is ongoing.

Boucher described how the reporting process feels broken when such a serious matter took more than a month to reach the parents.

“I wish the daycare had removed the staff member from contact with children immediately after the report was made. And I wish there were stronger safeguards in place so parents are notified right away when their child has been harmed,” Boucher said. “No parent should ever find out about something like this a month later. It’s too long, too dangerous and too traumatic.”

What’s more, she provided messages from Elevate’s owner showing that she didn’t tell other parents the truth about what happened. Soon after the family went to the police, Grant wrote to the center’s families to erroneously say that the state had not labeled the incident as abuse, according to copies of her message.

However, DHHS’ investigation was still ongoing at the time. DHHS then confirmed in a July 29 letter to the Bouchers that the state had determined their son was “a victim of abuse/neglect.”

Brewer officials went a step further than the state and recently denied Elevate’s license to operate in the city, effectively shutting it down. Photo by Erin Rhoda.

In addition, despite state rules requiring the center to notify parents immediately, Grant wrote to the center’s families that she hadn’t told the boy’s parents because she hadn’t wanted to interfere with the ongoing DHHS investigation and that she thought DHHS would have contacted the parents.

In her message to all the families, Grant apologized for “the incident itself but also for lack of notification.” She said she was updating Elevate’s policy to give DHHS 24 hours to contact “any parties before Elevate makes contact,” a process that still wouldn’t have met the state’s requirements. Grant denied a request from The Monitor for an interview.

Grant acknowledged in her message that the teacher had been too rough and also defended Sullivan, saying she had shown “incredible love, care, and the best interests of the children and families we serve” throughout her employment.

After closing its investigation, DHHS issued Elevate a conditional license on September 18 that would last a year. It would allow the daycare to continue operating but require it to follow the state’s rules to come into compliance.

Lindsay Hammes, a spokesperson for DHHS, said the state takes allegations of abuse and neglect seriously, and it investigates “to hold providers accountable and ensure the safety of the children in their care.”

It was the second time this year that the state had asked Elevate to correct its procedures. In February, DHHS had also issued a directed plan of action for the facility after it failed to report child-to-child sexual contact within 24 hours, get parent signatures on incident reports and supervise children at all times.

“The past mismanagement is part of what I am looking at for patterns of behavior,” Brewer police Chief Chris Martin told city councilors on September 23. “There were significant violations of lack of transparency to lack of reporting. Everyone is culpable.”

Brewer city councilors went a step further than the state. On September 26, they officially denied Elevate’s license to operate in the city. Six months after Boucher’s son was slammed to the ground, the child care center was forced to close.

“Knowing that this daycare will no longer be operating means other children will be safe, and that gives me peace in the middle of all the hurt,” Boucher said. “While the pain doesn’t go away, this decision is a powerful step toward healing and accountability.”

Beyond Elevate

Most investigations don’t result in a daycare’s closure. They also often don’t have video evidence to rely on, and the findings are less clear cut, meaning they may receive less public attention. Parents with other children at a facility, or who are considering sending their kids to one, may not find out about a DHHS case at all.

At a daycare in Portland, an infant went home with a severe injury, and no one mentioned it to his parents. Unlike Elevate, The Driscoll Child Development Center did not have a video camera recording what caused the 4-month-old baby’s arm to break above the elbow.

No one at the daycare told his mother, Jackie, about any injuries when she picked him up on Sept. 1, 2022, she said. She only took her baby to Northern Light Mercy Hospital that night because he kept screaming in pain when his arm was moved even slightly. An X-ray showed a broken humerus.

The Monitor agreed at Jackie’s request to only use her first name to protect her son’s identity.

It was the hospital, not the daycare, that reported the injury to child protective services. A pediatrician specializing in child abuse explained the fracture was likely inflicted.

“This fracture would have required forces far beyond any that would be encountered during normal play and activity or through routine care for a child of this age and development,” wrote the pediatrician with the Spurwink Center for Safe and Healthy Families. “An appropriate supervising caregiver would be able to provide some form of history as to how and/or when the injury occurred; no such history has been offered in this case.”

It took five months for a state investigator to clear the parents and confirm that a teacher at Driscoll was responsible, according to a notice from DHHS. The employee, Brynn Devou, appealed the finding. She told the state that she was one of three teachers in the infant room who all cared for 10 babies. They were all very busy, she wrote in a statement obtained by The Monitor, and she never saw anything happen that would have injured the baby boy, though he had been fussy throughout the day.

“I would never intend to hurt a child, I feel terrible that he was hurt and I am committed to making sure it never happens again,” she wrote.

Devou came to a deal in November 2023, more than a year after the baby’s injury. It required her to complete training over the course of a year and acknowledge that her “handling” of the baby “resulted in serious injury,” according to the agreement.

But the state acknowledged there was no evidence Devou hurt the baby intentionally. It agreed to keep a lesser finding of an infraction on her record, rather than a substantiated case, once she completed the terms of the agreement. (The proceedings were administrative and not handled in court. Devou was not charged with a crime.)

The lack of clarity shook Jackie’s family.

“Did he get picked up by the arms? Where were the daycare workers? Didn’t he cry a lot after? Didn’t anyone notice that moment? Was there no one else there as a witness if God forbid it was done on purpose?” Jackie wrote in a log she kept in the days following the incident.

She struggled, too, with the fact that other parents with children at the center were unlikely to know there had been an investigation. It wasn’t until April 2023 that the state sent the center a notice that it was planning to downgrade it to having a conditional license, which it would have to post in public view at the center.

Parents told The Monitor that they rarely look at the paperwork posted in their daycare and said they believe they should be personally notified about misconduct.

DHHS made its decision after three investigations into different violations at Driscoll, it wrote, including one where staff saw but didn’t report an employee who smacked a preschool-age child twice. DHHS wasn’t able to confirm whether the center told the child’s parents about the smacking, according to its summary of the violations.

The Monitor called and emailed Driscoll, but could not reach the owner, Idriss Kambeya, or the director, Lara Maloney, for an interview. Devou, who no longer works at the center, also could not be reached. Her attorney, Eric Thistle, declined an interview.

As for what happened to Jackie’s son, it merited a single line on the eighth page of the state’s nine-page directed plan of action: “On September 1, 2022, a Child Care Staff Member handled an enrolled four-month-old (4) Child in a rough manner that resulted in a broken arm.”

The brief description felt buried and insufficient, Jackie said. It didn’t capture the toll the process had taken on her family.

“I couldn’t even have completely imagined how broken the system was until I was in this position,” Jackie said. “I’ve been struggling with how to speak out and where I can make a difference because I don’t want this to happen to other children and parents. I truly believe the system needs fixing.”